background: In front of the border fence of Europe

In the Ukrainian part of Transcarpatia the European Union keeps away refugees

14.Jul.07 - By Stefan Dünnwald The Ukraine is a country shaken by political turbulences. And that not only because of its specific geopolitical position in the middle of the ambivalent "transit area" between European Union and Russia. While the Baltic States are firmly oriented towards the West and EU Member States since 2004, Belarus leans upon Russia closely and very strict. In the Ukraine both tendencies exist almost balanced. As a neighbouring country east of the European Union, the Ukraine is an important transit country on the way from the East to the West. Migration being no issue so far in Ukraine and the border towards the east still as pervious as ever, the situation at the western border changed a lot through the enlargement of the EU. These changes recently led to a downright "migration tailback" along the border of the EU towards Poland, Slovakia and Hungary. All these states made readmission agreements with the Ukraine, the EU followed lately. That's why the border police sends everyone back being taken up during an illegal border crossing, even refugees. Back in the Ukraine the illegal border-crosser is first arrested and then interned, for example in the detention camp in Pavschino in Transkarpatia. Via the UNHCR in Budapest an Kiew we got the permission to visit the prison in Chop and the detention camp in Pavschino. The Human Rights Organisation Pro Asyl initiated the research on detention camps in the western part of Ukraine.

Accompanied by Ferenc Köszeg of the Hungarian Helsinki-Comittee I head for Ushgorod, the main capital of the oblast (district or area) Transkarpatia, the most western tip of the Ukraine. The road from the border crossing point between Hungary and Ukraine is well built but it ends just before Ushgorod. A bridge is being restored, so we rumble on byroads, via little villages, along churches and a poor Roma camp towards Ushgorod. Ferenc asks our way in Hungarian. Transkarpatia belonged to lots of different nations over the last 100 years and so many of the inhabitants speak Hungarian. It is pitch dark when we reach a tiny, shady hotel someone recommended to us. With a few bottles of beer from the fridge we start to plan the next day. First of all we want to visit the prison in Chop, then talk to the migration office in Ushgorod and finally visit the detention camp in Pavschino in the afternoon. I wake up at night, outside the hotel countless dogs mark their territories, barking and howling.

The "Isolator" – the prison in Chop.

The next morning we chug along the same byroads back to the border. Albert Pirchak, the director of NEEKA awaits us just outside of the village Chop. Originally NEEKA ist a conservation group, but during the last years the association started to work in cooperation with the UNHCR and as a local partner in a project of the Caritas Austria. This project fights for the improvement of the conditions in refugee detention camps. Following Albert, we drive through Chop up to the garrison of the border army, where the prison for migrants is situated. A lieutenant colonel welcomes us in gruff ukrainian and hands us over to the director of the prison. Past the main building we reach a clean one-storey house. A board besides the covered entrance gives notice that the building was erected within the scope of the Caritas Austria project, financially supported by the EU. We enter the building and walk past the reception where the porter explains us the advantages of the building. First of all we see the sanitary facilities, the toilets and the showers. Not until late we discover that only the women and families in the left wing of the building can use these facilities. The men in the cells of the right wing of the building have no chance to have a shower. Ferenc demands to speak to the prisoners and we 're led into a cell with a single man from Moldawia.

The cell is about 8-10 square metres and gives room to 4 prisoners. There are two bunk beds along the right side and on the other side – separated by a 1,5 metre wall – is a urinal and a washbasin. The tiny window with frosted glass cannot be opened. Despite of the fan the air in the cells is sticky and stinks. The doors have metal fittings, bolts, a hatch and a peephole. The young man from Moldavia was taken up in the border area by Ukrainian borderguards. Normally he shares the room with three other migrants from Moldavia. are not here at the moment, during the day the prisoners are sometimes allowed to leave their cells. Our border police escort listens curiously until Ferenc orders them to leave the room.

The young Moldavian is imprisoned since 4 days and should get his notification the next day. This notification is equal for all migrants from Moldavia: they have to leave the Ukraine within 10 days and they have to pay a 60 Euro fine. However they can pay the fine in Moldavia as well. People from Moldavia don't need an entry visa for the Ukraine, but like everyone they have to fill out a form, giving the purpose and destination of their trip.

Right opposite in cell nr. 9 there are 4 Moldavians too. They even managed to cross the border but then were caught by the Slovakian border police. After a thorough questioning they were handed over to the Ukrainian border police within 24 hours. Although they asked for asylum in Slovakia they had been deported. They all seem composed and healthy, showing no signs of injuries or use of violence. Nevertheless they talk hesitatingly about beatings.

On principle the border troops care for the food supplies. The prisoners receive hot water three times a day, one warm meal per day. According to the prisoners the food is inedible although it is the same food the soldiers get. The Caritas cares for some additional supplies in form of crackers, convenience food, sardines or thunafish in cans. They also care for teabags, toiletries, toothpaste, soap etc.

After our conversation with the prisoners several border policemen await us in the conference room. We're allowed to ask questions. The informations are wordy but empty. The prison is not called "isolator" any more, the connotation was too negativ the spokesman of the troup says. It is now called "point" instead.

The term of confinement in Chop is 10 days at the most. After that time the prisoners are either deported, set free with the order of summary punishment (like the Moldavians we met) or transferred to the detention camp in Pavschino. If an application for asylum has been made this application is transferred to the migration office in Ushgorod. Above all people from Chechnya are deported. The guards remarke drily that they are brought to the train, transported directly to the russian border and given over to the authorities. The information that the border army hasn't got enough money for the train tickets seems to be outdated. There's enough money to pay for the deportations. We gather some more information but then Ferenc presses us to go. The migration office in Ushgorod is waiting for us. On our way back we notice that the main building is being renovated too. Before the Caritas started the EU project the prison cells were virtually holes. But even now it's not as good as it seemed to us first. What we didn't see was the courtyard for men: a concrete square with a roof made of reinforcing steel, resembling Guantanamo. And shortly after our visit the prison was so overcrowded that the prisoners had to sleep on the floor. Three at a time had to go to the toilet – if the guards had time.

Asylum? A question of bureaucratic order.

Back in Ushgorod we find the migration office of Transkarpatia in a small side street. The migration office deals with asylum applications in the region. The building is being renovated, too. Again we see the blue plate with the star wreath beside the door. Passing planks and tubs with mortar we walk up to the first floor and are welcomed by Mykola Towt, the manager of the migration office. He is affably and serves coffee. After a short introduction, saying how pleased he is with our visit, Mr. Towt gives us an intricate and long winded description of the Ukrainian mode of asylum. There are lists providing information about the number of people picked up in the border area. Most of them come from the former USSR, most of all from Moldavia. Then people from China, Bangladesh, Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, as well as people from Iraq, Somalia and other African states. Only 10% of them are women and very few kids. We inquire: why did none of the Chechen ask for asylum? Why didn't we meet any Chechens in the prison in Chop? The answer is evasive: It's the business of the border army, the migration office only deals with applicants for asylum. Every application arrives at this office and is proved. Then the asylum seeker receives a paper, valid for 15 days. We raise the objection that according to the border army every Chechen is deported immediately at the border. Mr. Towt leaves that unanswered, there might exist different informations. As far as we know from reports from Human Rights Watch it is a pure matter of luck, whether the border army accepts an application for asylum and if the application is eventually passed on to the migration office. Chechens come off badly with the Ukrainian border soldiers and they usually are deported even before their application is forwarded to the migration office. Mr. Towt escapes further requests by talking about identity cards. He gets a bundle of multi-coloured papers out of a steel locker and explains the process. Every stage of the application process requires a new document in a different colour. After a short while we feel that he takes us for a ride. Finally we get some sobering data. Out of 3000 people being picked up in the region, only about 380 had been able to apply for asylum. 80 of those applications were rejected immediately, 170 were admitted but rejected in a summary judgment. 115 applications were dropped and about 30 are still in process. The bleak record of the year 2005: not a single application for asylum in the region of Transkarpatia was successful. 2006 seems to be just as bad.

That's a matter of prioritization as well. The migration office in Transkarpatia has got only 8 employees, whereas the Ukrainian border army counts 40.000 soldiers, stationed in the region. It's true that the UNHCR urged the Ukraine to install an asylum system but it doesn't seem to be a serious suggestion. The priority is given to the defence of illegal migration, not to the right of asylum. The border army still draws its influence from former sowjet times whereas the new migration office has still to be established. That way despite the greatest efforts on the part of the UNHCR only little improvements had been made. At least 5 out of 8 employees are said to go regularly to Chop and Pavschino to take applications for asylum from there. Nonetheless the engagement of the employees plus the possibility for refugees to appeal to a court doesn't change the fact that the right to asylum in the Ukraine is far from being an option.

Perestroika – from the rocket launching site to the detention camp.

After a stop in a cafe having coffee and puff pastry we drive on towards Pavschino, the detention camp for migrants in Transkarpatia. Leaving the bumpy roads in Ushgorod we now move on southwards on a comfortable highway. First of all there is some paperwork to be done in Mukaschewo. It's raining heavily. Ferenc and I wait in the car while Albert takes our passports and runs to the gate of the garrison. He returns half an hour later, accompanied by two young soldiers with grotesquely big peaked caps. Altogether we leave the city, onto the country road heading south.

Soon a plain bitumenized path leads off the road into the forest. After a few kilometres we reach the area of the detention camp Pavschino. An iron fence is beaming blue from the distance. The rain had turned the entrance into a lakeland area. At the gate we are welcomed by several soldiers.

Accompanied by Albert and the escort with the big caps we first visit an adjacent building, canteen and advisory bureau arranged by the Caritas. There we meet a lawyer from NEEKA who talks to a refugee from Somalia. Since legal aid is allowed in the camp, applying for asylum has gotten easier. Twice a week a lawyer gives legal advice to the refugees. Some of the internees fled from poverty and lack of perspectives in their home countries. But most of them were put to flight by civil wars and the persecution through authoritarian states like the former CIS and numerous asian states. In Pavschino it is still not guaranteed that the applications for asylum are forwarded to the migration office by the border army. We decide to look around first and we promise to come back later. Albert shows us round. The camp owns a heating fuelled with wood. In case it works the temperature raises up to 15 degrees Celsius in winter, Albert smiles wryly. There's a television room too. Proudly it is said that satellite reception allows watching even Al Jasira. In the opposite room a ping-pong table is screwed together by three soldiers.

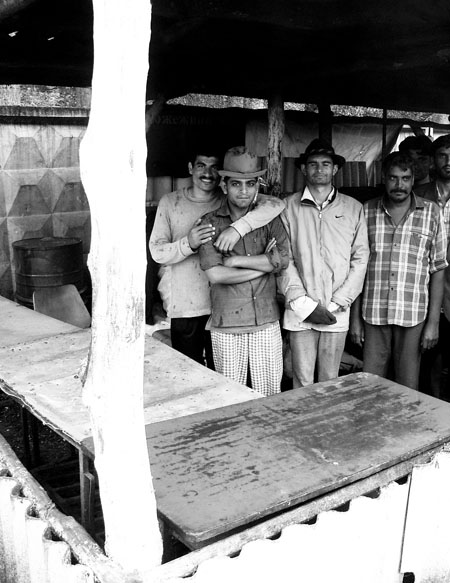

As we leave the building it starts to rain again. Under a tin roof in a corner of the camp stands a group of refugees, waving at us. Thick smoke rises from the shack drifting across the courtyard. As we come nearer they welcome us in English. This is the kitchen of the camp. A big black sooted field kitchen causes the clouds of smoke. There's macaroni for dinner a refugee explains and pulls out a drawer with steaming pots. There's always macaroni or buckwheat groats. A round dozen refugees edges forward. They come from Pakistan, India, Bangladesh - like most of the 407 prisoners we met at our visit in Pavschino.

As we walk across the courtyard we see only a few refugees. The main building is on the right hand side. In front of it there are little patches of plants, bogged down in mud at the moment. The main building used to be a house for the families of officers. Until the end of the seventies the area around Pavschino used to be a rocket launching site for the SS20. Later in the evening in Ushgorod Eduard Trampusch explains that the rockets were supposed to aim at targets in Belgium. Eduard Trampusch leads the project of the Caritas Austria for the improvement of the situation for migrants in prison. 80% of the money for the project comes from the EU and should be used for the improvement of food supplies, the installation of sanitary facilities and the provision of legal advice services. The Caritas cares for the drinking water supplies as well: it has to be fetched with lorries.

Ferenc stays with the refugees asking them about the circumstances of their arrest and how long they´d been arrested. In the meantime I stroll towards the main building. There´s a group of refugees standing under a tin roof in front of an adjacent building. Three telephones are fixed to the wall. For month these telephones are the only connection to the outside world but only for those with money. As I come closer to one of the entrances of the main building I understand why only a few refugees gather in the courtyard. The stairway is barred with an iron railing secured by a solid padlock. People are crowded in the dimness behind the bars. As I step forward to greet them they complain about the accommodation, the food, the always stale bread. They ask me about my telephone number and tell me in an English which is difficult to understand, that they are locked in because of our visit. Usually it is the other way round: they have to stay outside the whole day and are not allowed in the house.

Suddenly some of them start to besiege me to hand out the address of the Flüchtlingsrat in Germany, others complain again loudly about the bad food. Several guards had approached behind my back. But Ferenc and Albert arrive at the same time and the soldiers open the bars reluctantly. In a harsh voice one of the soldiers commands the refugees to clear the stairs and we follow them into the badly smelling stairway. Upstairs a narrow corridor leads into a room with about 25 square meter, packed with bunk beds and accomodating more than 20 refugees. Most of them come from South Asia, some from China, Vietnam and the Middle East. Several of them tell us that they'd been taken up by border police in Slovakia. Unisonous they say that they were arrested and questioned about their countries of origin and the travel route. Although they had applied for asylum they were deported to the Ukraine within 24 hours. Three of them tell us that they'd been beaten by slovakian border policemen and in Chop prison. None of them tells of beatings in Pavschino. This is not surprising thanks to the presence of the soldiers in the room. Amazingly enough many of the refugees speak russian fluently. Ahmed from Pakistan lived in Moskau for 7 years, operating two restaurants during that time. After the tax authority had confiscated his business for the second time he decided to migrate again. Seeking refuge in flight takes long sometimes and the destination is not always a western European country.

We visit another room where the bunk beds are crammed in even tighter. A sick man lies in one of the lower beds. Yes, he says, a doctor came but he didn't get any medicine. Nothing serious, the doctor said. One of the refugees folds back the blanket from the neighboring bed showing completely worn out sheets. Only the sick are allowed to stay within the building, the prisoners tell us. All the others have to linger in the courtyard. This way it is easier to control the prisoners one of the soldiers explains. One day the refugees had build an immersion heater out of iron parts of the beds to boil water for tea which led to a complete power failure. As a matter of fact there is no light. Supposedly this didn't happen yesterday for there are not even bulbs in the holders. We try to imagine how these 400 hundred men feel, living in a house without light. We're fed up with things and we even forget to look at the sanitary facilities, whose breath-taking smell we have met as we entered the building. We say good-bye to the refugees in the main building and walk back to the advisory bureau where the lawyer of NEEKA still talks to the Somali. It is nearly dark in the room by now. That puts the tv-room and Al Jasira into perspective. Briefly we talk to the man from Somalia who declares that he'd been persecuted by members of Al Quaida. Then we say good-bye to those two as well. On our way out we notice that in the meantime the soldiers managed to fix up the ping-pong table and started to play. I start to doubt whether the improvements financed by the Caritas really reach the prisoners.

It started raining again. The whole courtyard is filled with muddy puddles. Walking towards the exit we pass three military tents, additional accomodation for refugees. According to reports from the Caritas there had been more than 500 prisoners in Pavschino in the summer of 2006. They had problems with accommodation and quarrels about the drinking water supplies. A group of refugees comes out from one of the tents and keeps us once more. A German speaking man tells us that he has lived in Switzerland for several years. Puzzled I ask how he happened to end up in the Ukraine. Via Pakistan is the lapidary answer. In a loud voice that even the guards can hear him he complains about the sickening conditions in the camp and that the soldiers beat them up. Another one complains of his obstinate cough and that the medicine doesn't help. In sheer outrage the small group stands behind the fence in the rain. The soldiers dismiss the complaints of the refugees out of hand: " Nothing but lies", they say.

Our signature is required at the guardhouse and then we walk on to the car. We will drive back to Hungary the next day. With a little luck, after 6 months of imprisonment the men in Pavschino will be on their way to western countries too, leaving Pavschino behind. If they have bad luck they will be taken up again and imprisoned for another 6 months. Our escort accompanies us back to the highway to Mukachewo and waves good- bye. Early the next morning we are back on our way to Chop. There is a long queue at the border crossing. Many Ukrainians search their way to the western countries as well. Since Hungary and Slovakia became members of the EU in 2004 the trade across the border or the search for work in neighbouring countries is almost paralized. But meanwhile in parallel with the military buildup of border controls there had been easements for Ukrainians too. Through various channels the EU finances structural activities and migration control in the eastern neighbouring states. A delegate of a Slovakian NGO reported that up to 2006 the Ukrainian border army refused to take back refugees taken up in Slovakia. However things became better now.

more information: first published (in german) in hinterland